There has been a lot said about Kevin Rudd’s petition for a ‘Royal Commission to ensure a strong, diverse Australian news media’. There was Rod Tiffen’s comment that Mr Rudd then responded to, and a host of other reports including this piece from Margaret Simons on the thinking behind the petition. And Zoe Samios ran this piece about the difficulty of pinpoint the reach of News Corp in Australia.

There is certainly a lot of history between Mr Rudd and the main targets of his petition – Rupert Murdoch and News Corp – but maybe we can accept that, regardless of Mr Rudd’s views on News’ reporting on the ALP, there are some legitimate questions here about concentration of ownership and media responsibility.

Philip Napoli’s recent book, ‘Social Media and the Public Interest’ asks whether public interest objectives that traditionally attach to news media can be applied to social media and digital platforms. Napoli observes that, just as oligopolistic markets tend to undermine the rationale for a ‘marketplace of ideas’, the idea that ‘counter speech’ is the answer to false news is looking more shaky in a global, digital environment. While there are other reasons for rejecting the marketplace of ideas approach (as our colleague, Kari Karpinnen explained so well in Rethinking Media Pluralism) it still has influence in Australia, particularly in our fragmented approach to media standards.

But while Napoli has asked about applying public interest principles to social media, in Australia it seems we have enough problems applying it to traditional media. The ‘Save our Voices’ campaign, launched by the three regional broadcasting networks with Australian Community Media and fronted by Ray Martin, wants the removal of the one-to-a-market cap on commercial television licences. With the repeal of the cross-media rules and the national audience reach rule, the licence cap is the cornerstone of structural diversity in Australian commercial media. It means that in most licence areas, there will be at least three commercial media operations. Broadcasting law no longer stops mergers between local newspapers, television and radio, and neither does it regulate ownership of online news sites or other digital media, pay TV or national newspapers. In the concentrated Australian media market, there must be an alternative to further concentration in regional Australia.

It was good, then, to see Michelle Rowland, the shadow communications spokesperson, speak of the need to rethink regulation in a way that ‘takes account of algorithms as much as ownership’ and that considers both media plurality and industry sustainability. She also referred to the research the ACCC commissioned from the Centre for Media Transition – which drew on the work we’ve been pursuing in the Media Pluralism Project – showing the need for ways of measuring media plurality that take account of aspects such as consumption and impact. While the one-licence for TV and two-licence for Radio caps on ownership are important, these shouldn’t be the only two tools (the other being the local area points test) that we have available for assessing plurality. That, of course, is what we’ve been working on at the Media Pluralism Project, and we hope to have a new tool for demonstration very soon.

As we’ve argued before (and as has Des Freedman et al. at the Media Reform Coalition in the UK), in order to maintain and ‘future proof’ a media ecology that is capable of sustaining a range of diverse and conflicting voices and perspectives some genuine media reform is urgently required. At a minimum this would include:

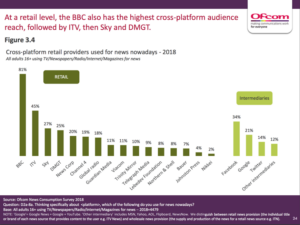

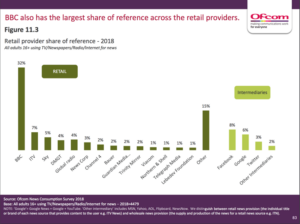

- A plurality/diversity measurement framework that takes into account cross-market audience share in traditional (TV, Radio, Newspaper) and online news markets. This framework needs to include various methodologies that uses quantitative measures of reach and consumption, and qualitative data on the wider media agenda impact;

- Regular reviews by an independent regulator to evaluate relevant thresholds based on these cross-media market audience shares. These thresholds would be actively monitored to guide intervention and remedies aimed at promoting a diverse media ecology at the national and local level including in relation to public service media provision;

- News distribution on digital platforms/intermediaries should be taken into account in assessments of diversity including the impact of algorithms on news brand availability (and the public affairs content of those brands). This kind of monitoring by an independent regulator would, using appropriate metrics, assess whether or not platform algorithms are favouring particular news providers and voices over others; and, very importantly,

- In the event of mergers between media organisations an independent regulator should be able to apply a public interest test to assess whether the particular combination of media groups will benefit audiences in terms of the provision of public affairs content in the markets if the transaction were to proceed.